How much have sanctions, and other politically induced restrictions on economic activity, affected the Venezuelan economy? How much of the country’s decline can be attributed to these causes, as opposed to the more standard causes of poor policies and external shocks? In this paper I offer a quantification of the effect of alternative causes. The bottom line is that around half of the country’s economic contraction between 2012 and 2020 can be explained as a result of sanctions and other politically induced restrictions such as the withdrawal of government recognition.

What is the true balance of forces in Venezuela’s National Assembly?

An analysis of legislator preferences as expressed by roll-call votes as well as public statements finds that Juan Guaidó would have received 86 votes against Luis Parra’s 71 in a full session to elect the President of the Venezuelan National Assembly. While still maintaining the support of a plurality of legislators, these calculations show that Guaidó’s ability to achieve the needed quorum for a valid session is now dependent on the votes of Amazonas legislators, whose validity is contested by Maduro’s forces. We estimate that the opposition has lost 29 legislator votes since the 2015 elections through a combination of judicial actions against it and its own errors in coalition management.

Francisco Rodríguez[1]

At around noon on Sunday, January 5th, a group of dissident opposition legislators voted with representatives of Nicolás Maduro’s socialist party to elect a new President of the National Assembly of Venezuela. The legality of the vote was immediately contested by the country’s opposition, which convened an alternate session of the Assembly to re-elect Juan Guaidó for another term as President of the same Assembly. As a result, Venezuela now has two boards that claim to be the legally elected leaders of its Legislative Power.

Importantly, maintaining the Assembly’s presidency is key for Guaidó’s claim to being the legitimate interim president of Venezuela, which relies on a constitutional provision according to which the head of the Legislature will hold the interim office of the presidency in the absence of an elected president at the start of the constitutional term. The country’s opposition, as well as a significant part of the international community, does not recognize the 2018 presidential elections as free and fair and thus claims that there is no legitimately elected president for the 2019-25 presidential term in Venezuela.

However, there is still considerable uncertainty regarding exactly what happened on that day and what it tells us about the balance of power within the legislative branch. Both groups claim to have had a majority of legislators present in the sessions at the time of the vote. Parra claims to have obtained 81 votes in a session attended by 150 legislators[2] but has yet to produce attendance records. Since no roll-call vote was taken (voting was conducted by a show of hands)[3], there is no direct way to verify the number of legislators present or the number of votes obtained by Parra.

On the other hand, focusing on the balance of votes within the chamber is not necessarily meaningful given the evidence that some legislators were blocked from entering the chamber.[4] Because of the way in which the National Assembly’s rules of debate (originally penned by Chavista-controlled legislatures) are written, it is technically possible to elect a National Assembly President with the support of as few as 43 legislators. This is because while 84 legislators (more than half of the chamber’s 167 representatives) must be present for there to be a valid quorum, the board of directors of the Assembly is chosen by a simple majority of those legislators present. Thus, it is not difficult for a group that controls access to the chamber to assure itself of a majority of legislator votes.[5]

VENEZUELAN ARITHMETIC 101

Analysis of the roll-call vote given in the evening session is more informative. Since the session was broadcast live and is publicly available[6] there is no doubt that the legislators referred to actually cast their votes. Therefore, we can use the roll call vote to infer legislators’ support for Guaidó at present and at the time of the vote.[7]

Our primary focus of interest is estimating the size of the coalition supporting Guaidó, for which the January 5 roll-call gives us the best direct evidence. Understanding how many votes Guaidó commands is only part of the picture; in order to know the overall balance of forces we would also need to estimate Parra’s votes. We attempt to estimate Parra’s support further below, though the absence of a roll-call vote makes that exercise more tentative. However, there is one very relevant sense in which estimating the size of the Guaidó coalition in itself is relevant: to assess whether he commands the majority of votes necessary for the required quorum for the Assembly to session and take valid decisions, which is 84 legislators.

In total, 100 legislators took part in the vote held during the alternate session which re-elected Guaidó held on the evening of January 5th in the headquarters of the pro-opposition newspaper El Nacional. All of these voted for the slate of candidates headed by Juan Guaidó.[8] It is crucial to understand that this does not imply that Guaidó would have counted with 100 votes in a regular session of the National Assembly (which is what we seek to estimate). Several of the legislators present at the session re-electing Guaidó were substitutes of principals whose votes may have differed from theirs. In fact, precisely because of the regime’s efforts to co-opt legislators has been focused on principal legislators, there are several cases in which we know that the principal sided with Parra (or was unwilling to support Guaidó) while the substitute supported Guaidó. In a regular session of the Legislature, the substitute’s vote intention would be rendered irrelevant if the principal were to show up.

In fact, it is technically possible for two legislatures to function in parallel and for both to hold sessions that satisfy the valid attendance quorum of more than half of legislators even if they have no participants in common. This will happen if they are both partially stacked with substitutes whose principals participate in the alternate session. In normal conditions, it would correspond to the judiciary to decide which of the two sessions has been convened constitutionally. In Venezuela, where the sides to the conflict do not recognize the same judiciary, there is no straightforward way to resolve this conflict.

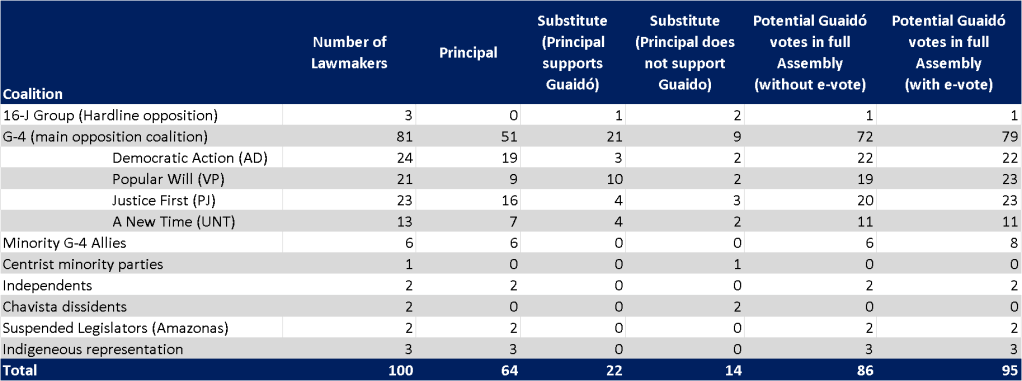

Table 1 shows the breakdown of the 100 votes obtained by Guaidó in the evening session by the legislator’s condition (principal or substitute) as well as, in the case of substitutes, by whether the principal would have voted for Guaidó. We also provide a subdivision by party or legislative group of the legislator who voted in the session. Of the 100 legislators, 14 were substitutes of legislators who did not support Guaidó. These are either legislators who explicitly voiced their support for Parra (11) or who belonged to parties that had announced that they would not back Guaidó’s re-election (3). This means that in a regular Assembly session in which legislators not supporting Guaidó were present, Guaidó would have counted with the support of only 86 legislators, two votes more than the minimum majority of 84.

Table 1: Breakdown of January 5 evening vote and hypothetical plenary votes

However, 3 of those 86 legislators represent the state of Amazonas.[9] Their suspension by the Supreme Court’s Electoral Chamber shortly after the 2015 election on fraud allegations is precisely what set off the protracted conflict of powers between the judicial and the legislative branches that continues to this day. If we exclude those legislators, then Guaidó’s support would have fallen to 83, below the 84-vote threshold for a simple majority and valid quorum. Note that this does not necessarily mean that Guaidó would have lost the vote for National Assembly President, as these 83 votes may still have exceeded the number of votes in favor of Parra (who himself claims to have obtained only 81 votes). But it does mean that Guaidó would not have had enough votes to sustain a valid quorum.[10] This is likely the reason why Guaidó spent so much effort on an unsuccessful attempt at trying to get all legislators, including the Amazonas deputies, into the chamber on the morning of January 5th.

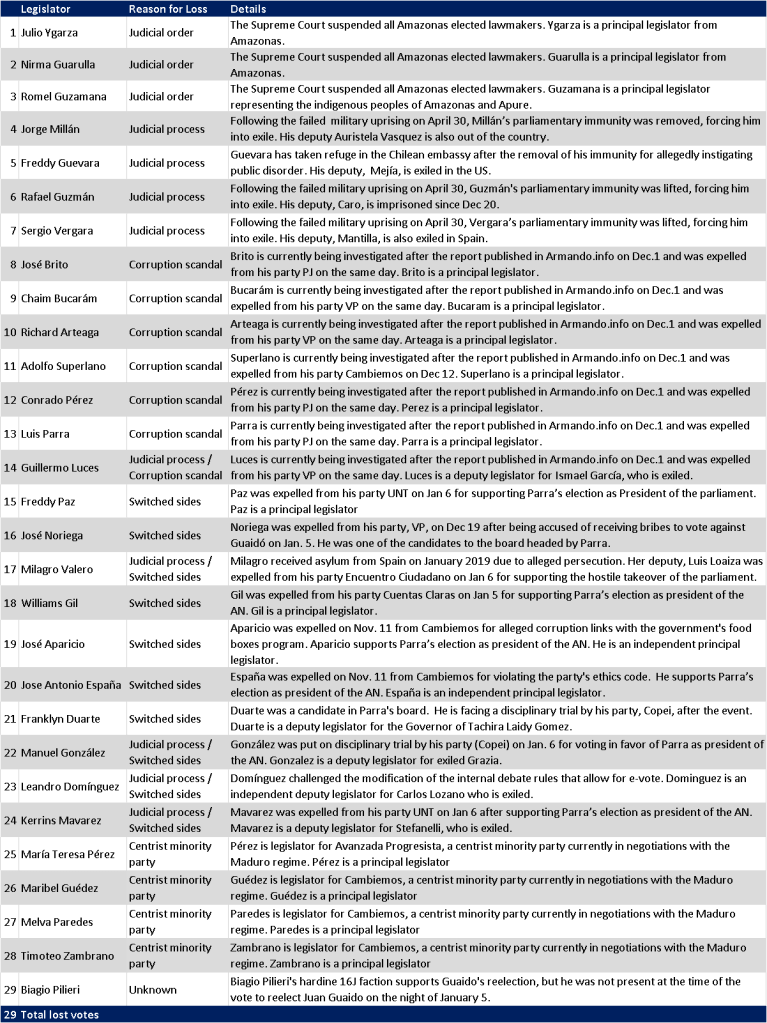

How many votes is Parra likely to have mustered? In Table 2 we estimate the vote of a hypothetical plenary session in which all principals in the country joined the session. We assume that e-vote is not permitted (we return to this below). We also assume that all PSUV legislators would have voted for Parra, as well as all opposition dissidents who have been expelled from their parties for corruption investigations or have voiced their support for Parra. However, we assume that centrist minority parties (AP and Cambiemos) would have abstained.

Our results are summarized in Table 2. If the Amazonas deputies had been allowed to vote, Parra would have gotten 71 votes and lost to Guaidó’s 86. Without the Amazonas legislators, the difference would fall to 83-70. Note that there are four empty seats and six legislators who would have abstained. Therefore, whatever the scenario, it appears that Guaidó would have won the vote by a comfortable margin of 13-15 votes.[11]

Table 2: Hypothetical balance of forces in plenary vote (without e-vote)

Given uncertainties about legislator loyalty, it is possible that the actual number of votes could have been different if the session had actually been held on Sunday morning. For example, the hardline 16-J faction, which voted for Guaidó in the evening session, had previously threatened not to vote for Guaidó, whom they charge with being too soft on Maduro. Recently, they had refused to vote for a proposal to change the rules of debate to permit electronic voting sought by Guaidó and approved on December 17. If their threat had effectively materialized, then Guaidó’s 86 potential votes would have fallen to 83, and to 80 without the Amazonas legislators. Alternatively, there are several principal legislators who are in principle pro-Guaidó and are not in exile but nevertheless did not show up to the January 5th evening session despite having no apparent physical impediment to attending. Their failure to show at the vote introduces uncertainty as to how they would vote in a full session of the Legislature.

On the other hand, if Guaidó had fallen below the required threshold he would have likely invoked the e-vote provision approved on December 17 allowing legislators to cast virtual votes. We estimate that this would have given him 9 additional votes, taking his majority to 95 votes (92 without Amazonas).

WHERE DID ALL THE OPPOSITION VOTES GO?

The bottom line is that while Guaidó still would in all likelihood have comfortably won a fair vote for the presidency of the Assembly, he commands the support of only around half of all legislators, making his coalition vulnerable. This is perhaps the more notable fact that surfaced out of the tumultuous January 5 sessions. Over the course of the past four years, the opposition’s majority has fallen steeply from the 112 legislators it won in 2015 to 86 legislators (83 without the Amazonas deputies). How did this happen?

The answer is a combination of persecution, persuasion, exhaustion and mistakes. While some legislative seats have been lost as a result of overt and explicit actions by the judiciary, others reflect voluntary defections by legislators who were originally elected in an opposition slate and who have decided not to back Guaidó, and others reveal genuine dissent within opposition ranks.

Table 3 lists the 29 legislative seats lost by the opposition during the past four years. Seven of these were lost as a result of judicial decisions. This includes the 3 Amazonas legislators whose election was invalidated by the Supreme Court’s electoral chamber and 4 seats which have been rendered vacant as a result of political persecution as both principal and substitutes are in exile, jail, or otherwise impeded from attending.

Table 3: Reasons for individual legislator losses by Guaidó coalition

But this only explains around one-fourth of the loss of seats. The remaining loss of votes shows a more conventional pattern of defections and dissent. Six votes were lost as a result of the expulsion of legislators that took place in November of last year after investigative news site Armandoinfo published a report containing allegations of wrongdoing. Another six legislators explicitly defected, announcing that they would back Parra despite still belonging to parties that support Guaidó. Four legislators belong to minority centrist parties that strongly disagree with Guaidó on key policy and strategic issues such as economic sanctions or the boycotting of elections (both of which are supported by Guaidó but rejected by large segments of voters) and have decided not to back him. Five legislative seats were lost by a combination of reasons, where the principal has gone into exile and the substitute switched sides. One additional legislator (Biagio Pilieri) showed up on Sunday evening’s session but did not vote for unknown reasons.[12]

WAS THE LOSS OF LEGISLATORS INEVITABLE?

It is not unusual for authoritarian governments to be able to co-opt large parts of their opposition. Because autocracies have unbridled control over the use of force and significant economic levers, it is easy for them to generate powerful incentives to sway some elected politicians. To a certain extent, what is surprising is that Maduro was not able to use these tools more effectively in the past, and that it is only recently that he has proven able to achieve large defections from the opposition.

But it is not enough to simply look at Maduro’s actions to explain the large decline in opposition support among legislators. If we seek to understand the magnitude of the parliamentary losses experienced in 2019, it is also important to consider some of the strategic decisions made by Guaidó and his governing team. Holding together coalitions is a complex task, and there is evidence to suggest that some of the strategic choices made by the Guaidó administration may have contributed to accelerating the rate of legislator attrition.

Coalitions are typically held together by a combination of policy concessions and appointments. It is common for coalitions to include actors with different viewpoints on key policy and strategic decisions. These actors are often persuaded to continue to support the coalition through the deployment of selective incentives. Because it is difficult to maintain everyone happy on central policy issues (such as whether or not to negotiate with the regime), positions on subsidiary policy dimensions can play an important role in holding together a coalition. So will appointments to key public offices, which are often remarkably effective in getting politicians to change their policy views.

During his administration, Guaidó has made relatively few appointments to public office, presumably out of concern with creating positions with no effective power. He also has not tapped the funds in bank accounts of the Republic or PDVSA that were transferred to his management as a result of his recognition by the United States (except for very limited purposes). Both of these decisions have diminished his capacity to offer the necessary selective incentives to hold the coalition together.

When the Guaidó government has made appointments, it has been much more likely to choose technocrats than political figures. To take one example, when a Debt Restructuring Advisory Commission was appointed in July 2019 and tasked with issuing general guidelines for dealing with the nation’s debt, it was integrated by two academics and a former Wall Street analyst. Notably, it did not have any representatives from the National Assembly’s Finance Commission, which had been overseeing and investigating debt issuance decisions since 2016.[13]

If we consider the list of opposition legislators that openly backed Parra, it is striking that of the 18 legislators (14 of which are principals), none is from the capital region[14]. In stark contrast, the two highest ranking parliamentary appointees of Guaidó (Foreign Minister Julio Borges and UN representative Miguel Pizarro) are legislators who represent districts of the country’s capital. Greater geographic balance and emphasis on regional issues could have helped Guaidó deal with the discontent among legislators from the provinces.

There is also the issue of how to deal with dissidence. When in September of 2019, a number of centrist minority opposition parties announced that they had accepted to participate in negotiations with the Maduro regime, the reaction of the Guaidó team was to strongly attack them for entering into a “false dialogue,” claiming that the government was trying to use them to create a “tailor-made opposition.” [15] It is not surprising that these parties, while refusing to back Parra’s candidacy, also refused to vote for Guaidó on the evening of January 5th.

Guaidó’s dissidence problems are not limited to the centrist parties. They have also had to do with reining in hardliners. As we noted above, the 16-J faction had threatened not to vote for Guaidó on January 5th and only seems to have changed its mind after that morning’s events. Relations have been tense with this hardline faction for some time; for example, the group has systematically complained that Guaidó violated debate rules by impeding discussion of topics on which 16-J dissented from the majority.

The large attrition in legislative support should also lead to a reconsideration of the effectiveness of individual sanctions in spurring regime change. The selectiveness and conditionality of individual sanctions has often been touted as one of their advantages. When on April 30th, the commander of the National Intelligence Service sided with a failed military rebellion against Maduro, the Treasury Department promptly removed sanctions on him, citing the case as an example “that U.S. sanctions need not be permanent and are intended to bring about a positive change of behavior”[16] However, the fact that the opposition has lost at least 17 congressional seats through defections (and gained none) over the past year precisely as these sanctions intensified suggests that this tool is at best ineffective – and at worst counterproductive – in weakening the governing coalition.

It may well be that the events of the past few days will strengthen Guaidó – at least for the time being – and lead opposition groups to rally around him in the defense of the last bastion of democratic institutionality. Yet unless the opposition leadership revises its approach to dealing with intra-coalition differences and its international allies reconsider their approach to engaging with the regime, there is a risk that the problems that generated this large attrition in legislative support will continue to weigh on the prospects for real democratic change in Venezuela.

Notes

[1] Director, Oil for Venezuela and Visiting Professor, Stone Center for Latin American Studies, Tulane University. E-mail: frodriguez@oilforvenezuela.org, frodriguez1@tulane.edu.

[2] Luis Eduardo Parra R (@LuisEParra78). “Como cada #5Ene, el día de ayer, la Asamblea Nacional eligió una nueva Junta Directiva de conformidad con la Constitución y el Reglamento de Interior y de Debates, donde obtuvimos 81 votos de los 150 diputados presentes.” [As in every January 5, yesterday, the National Assembly chose a new board in compliance with the Constitution and the Internal Debate Rules of the Assembly, were we obtained 81 votes from 150 lawmakers present]. January 6, 2020 3:42pm. Tweet. However, the government TV station Telesur had originally reported that 140 legislators were present. teleSur English (@telesurenglish) Luis Eduardo Parra has been elected president of #Venezuela’s National Assembly with 140 legitimate votes. January 5, 2020 3:08pm. Tweet. Constitutional Convention President Diosdado Cabello, in turn, claimed that an opposition legislator had admitted there were 127 legislators in the session. Cabello respalda “legitimidad de la directiva autojuramentada de la AN” [Cabello backs the self-proclaimed AN’s legitimacy]. TalCual, January 6, 2020.

[3] A show of hands vote is customary by National Assembly rules and can only be replaced by a roll-call vote if a lawmaker requests it. (Article 92 of the AN internal debate rules states that all votes are public, while article 94 stipulates that public votes are initially by show of hands, unless a lawmaker asks that it be done through roll-call). By Parra’s own count, however, the difference would have been of approximately 10 legislators, suggesting that the vote was close enough so as to make it difficult to ascertain who had the majority without a roll-call.

[4] There is significant confusion as to whose access was being restricted by the National Guard. Government spokespersons claim that access was restricted only to the Amazonas legislators and to others who had arrest warrants issued against them(GNB y PNB se guían por lista de diputados «inhabilitados» para permitirles ingresar al Parlamento [GNB and PNB use an “disqualified” lawmaker list to decide if they can enter Parliament]. NoticiaAlDía, January 5, 2020. Also see GNB impide acceso a Juan Guaidó a la sede de la Asamblea Nacional [GNB impedes Juan Guaidó from accessing National Assembly palace], El Nacional, January 5 2020.), while the opposition claims that more legislators, including Guaidó, were restricted from access to the chamber. As we will show, an actual vote would have been tight enough that even just the Amazonas restrictions would have been enough to tilt the balance.

[5] In principle, opposition legislators could have left and broken quorum, as by Parra’s own admission he has the support of less than 84 legislators. It is likely that the reason why the show of hands vote was taken at an unexpected moment was precisely to make it difficult for the opposition to try to break quorum.

[6] EN VIVO – Elección de la nueva directiva de la Asamblea Nacional 2020. [LIVE – Election of the new AN 2020 board]. Youtube, January 5, 2020.

[7] Since legislator preferences may have changes as a result of the political events on the past few days, the January 5 roll-call is most informative about preferences at the time of that vote; nevertheless, unless preference changes have been too great, it should still serve as a reasonable proxy for support at the present time.

[8] One legislator, Biagio Pilieri, was at the session but left before his turn to vote. If we include him, attendance would be 101.

[9] One of those legislators, Romel Guzamana, represents the indigenous population of the Southern region of the country, which includes Amazonas and Apure. Indigenous peoples have separate congressional representation as per article 125 of the Constitution.

[10] The National Assembly’s rules of debate do give the presidency enough latitude to incorporate substitutes when the principal is not present. This means that if Parra’s supporters had tried to filibuster the vote, Guaidó could have incorporated the substitutes and in principle obtained the same 100 votes as in the evening session. Nevertheless, while Guaidó could have managed to get re-elected legally, it would have been as a result of his authority to decide on the incorporation of substitutes, illustrating the fragility of the arrangements. The threshold of 84 legislators in a full vote is meaningful because it implies that the result of the election is not conditional on the control by the Assembly’s presidency of the process of incorporation.

[11] Is it possible that Parra obtained the 81 votes he claims in the morning session? To do so, he would have had to gain an additional 11 votes. We have not been able to identify the positions of opposition substitutes, but it is not impossible for there to be 11 substitutes from opposition, centrist or Chavista dissident votes that may have also been swayed by the government. Nevertheless, we underscore again that a vote held while limiting access to the chamber has relatively little legal or normative significance.

[12] Pilieri has later claimed that he fully supports Guaidó (Bloque Parlamentario 16 de Julio (@fraccionAN16J) “2/2 #5Ene @omargonzalez6: Aunque la Fracción 16J tenia acordado abstenerse el día de hoy, decidimos de manera patriota apoyar a esta Junta Directiva” [2/2 #Jan5 @omargonzalez6: Though the 16J coaltion had agreed to not vote today, we have patriotically decided to support this Board], January 5, 2020 6:17pm) so he would potentially raise the total of votes to 87 (84 without Amazonas). Nevertheless, we prefer to hold to the strict criterion of observable votes cast rather than expressed voting intentions. The rationale for this criterion is that legislators could have multiple incentives to dissemble, making it remarkably hard to gauge voting intentions from public statements when these contradict the vote cast. Our methodological choice should not be taken as a judgment of this specific legislator’s loyalty to the opposition cause, on which we think there is a reasonable case that he can be expected to continue siding with the opposition.

[13] Although an expanded commission was created on August 13 to include some legislators, our discussions with market participants indicate that the role of these legislators in debt talks has been nonexistent.

[14] We count 18 legislators instead of the 17 in Table 3 to reflect the case of Lucila Pacheco, Zulia legislator originally elected as a substitute PSUV candidate who then joined the opposition yet now supports Parra. This vote is not a net loss because it originally belonged to PSUV. Rather, it is a vote that was initially gained and then lost.

[15] Julio Borges: aquellos que se presten al falso diálogo no representan a Venezuela. [Julio Borges: those who partake in the fake dialogue do not represent Venezuela]. America Digital news, September 19, 2019.

[16] Treasury Removes Sanctions Imposed on Former High-Ranking Venezuelan Intelligence Official After Public Break with Maduro and Dismissal. U.S. Department of Treasury, May 7, 2019.

A Peace Prize That Brings Venezuela Closer to War

By throwing the moral authority of the prize behind an advocate of the use of force, the Nobel Committee’s decision makes a peaceful, negotiated solution to Venezuela’s conflict less likely.

Last week, the Norwegian Nobel Committee awarded the 2025 Peace Prize to María Corina Machado—a leading figure in the country’s opposition to the authoritarian rule of Nicolás Maduro. Ms. Machado’s courage and steadfastness in the struggle for Venezuelan democracy deserve recognition. However, her support for the use of force to achieve political change made her choice as a Peace Laureate paradoxical and troubling.

One year ago, Ms. Machado galvanized and electrified Venezuelans long accustomed to viewing their country’s rigged elections as meaningless. Defying government persecution and harassment, she urged citizens to use the ballot box to challenge Mr. Maduro’s authoritarian rule and helped organize a vast network of political activists who collected tally sheets showing that the opposition candidate, Edmundo González, had defeated Maduro (Machado herself had been barred from running for the presidency). As she said with humility upon learning of the award, the prize should be seen as honoring the millions of Venezuelans who mobilized to demand democratic change.

Yet the Nobel Peace Prize is not a prize for courage, nor for the defense of democracy by any means. And Machado’s public statements—as well as her silences—in the week after receiving the prize demonstrate why she was an inappropriate recipient for an award that is designed to reward work towards the peaceful resolution of conflict.

In the week since Machado was awarded the Prize, Venezuela and the U.S. have edged closer to an all-out armed conflict. The Trump administration has continued to sink boats near Venezuela’s coast, resulting in the deaths of at least 27 persons whom it has accused—without proof—of being engaged in the narcotics trade. The president has stated that land attacks on Venezuelan soil are under consideration and acknowledged that he has authorized covert CIA operations in Venezuela, which typically involve destabilization and the targeting of political figures. On Wednesday, two US bombers circled off Venezuela’s coast in a pattern that, when mapped, formed a crude obscenity — a clear provocation intended to elicit a response from Venezuela’s Air Force which could then provide a pretext for escalation of the conflict.

Even after receiving the Nobel award, Machado has expressed her explicit and open support for these operations, going as far as dedicating her prize to President Trump along with the Venezuelan people, while praising him for “addressing this tragic situation in Venezuela as it should”, characterizing the strikes as actions of “law enforcement” and claiming that the opposition had long requested such action. When asked whether she supports an invasion of Venezuela, she has deflected the question, claiming that “Venezuela already lives an invasion” and that instead it needs a “liberation.”

The Nobel Peace Prize is not a prize for courage, nor for the defense of democracy by any means. It is meant to recognize efforts towards the peaceful resolution of conflicts.

None of this is surprising. Ms. Machado has also long been a proponent of the use of military force to depose the government of Nicolás Maduro. In 2020, she requested that the opposition-controlled National Assembly authorize foreign troops to enter Venezuela as part of a multilateral operation to take control of territory and disarm government forces. Even after receiving the prize, she told Spanish newspaper El País that in order to confront a tyranny, “moral, spiritual and physical force” were needed and that “putting force first” and a “credible threat” of military action were fundamental for producing political change.

Also concerning is Ms. Machado’s refusal to condemn the Trump administration’s violations of Venezuelans’ basic rights. Earlier this year, U.S. authorities deported more than 200 Venezuelan nationals to a Salvadoran prison, accusing them with scant evidence of belonging to the Tren de Aragua criminal network while denying many of them due process on the pretext that they were enemy combatants in an invasion of the U.S. Machado endorsed the deportations plan prior to its implementation, and remained silent even as evidence mounted that Venezuelans’ rights were being violated.

Machado’s silence regarding the extrajudicial killings of Venezuelans in international waters is all the more striking given the growing consensus among human-rights groups and legal experts as to the illegality of these actions. According to sources quoted by the New York Times, concerns over the killings appears to have played a role in the unusual decision of the head of the US Southern Command, Admiral Alvin Hosley, to step down after only one year of his three-year term.

Machado’s silence in the face of forced deportations and extrajudicial executions of Venezuelans reveals a disturbing choice to make the rights of Venezuelans secondary to a political objective.

Ms. Machado has also long supported economic sanctions on Venezuela. While she has argued that these sanctions are needed to deprive the Maduro regime of resources, the evidence shows that they have contributed to generating the largest peacetime economic collapse in World history and the largest migration waves ever seen in the Western hemisphere.

The Nobel Peace Prize was established in 1895 to recognize those who advanced fellowship among nations, worked toward the abolition or reduction of standing armies, and promoted peace congresses. Over the years, the Nobel Committee has interpreted this mandate broadly, honoring both world leaders who have led efforts to end conflicts and human rights and democracy activists committed to achieving change through peaceful means. The prize to Ms. Machado breaks with both traditions by honoring a figure known for her advocacy and support for the use of force to pursue political change.

Perhaps the greatest risk from this award is that, by throwing the moral authority of the prize behind an advocate of a hardline stance toward political change, it will make a peaceful, negotiated transition less probable. The award comes at a time when there is an open debate, both in Venezuela and in international policy circles, regarding the best strategy to promote democratic change. Machado’s support for external military action and her opposition to any negotiation that does not result in the complete ouster of Chavismo from power put her at one end of that spectrum. Others have pointed to the need for continued organized peaceful resistance, electoral organization, and negotiations focused on institutional reforms that make coexistence with Chavismo possible as more viable and realistic strategies for political change.

The Committee could have honored Venezuela’s democratic movement by awarding the prize to the valiant activists who collected the tally sheets that offered proof of Mr. Maduro’s defeat last year.

The Nobel Prize Committee could have decided to honor Venezuela’s democratic movement by awarding the prize to the valiant activists who collected the tally sheets that offered proof of Mr. Maduro’s defeat last year. By choosing to back one leader within that movement—and precisely the leader who is most opposed to political compromise— they may have inadvertently made a political solution less probable and a war more likely.

Only a handful of times has the Nobel Committee decided to bestow the prize on a political leader of an opposition to an authoritarian regime. Perhaps the closest example is the 1983 Nobel award to Lech Walesa, which played a key role in focusing international attention on Poland and in making possible the negotiated agreements leading to what remains the most successful economic and political transition to a market democracy in Eastern Europe. Like Walesa, Ms. Machado now faces a crucial choice: whether to use her stature to reconcile a fractured nation, or to deepen its divisions.

Un premio de la paz que acerca a Venezuela a la guerra

Al respaldar con el premio a quien ha abogado consistentemente por el uso de la fuerza, la decisión del Comité Nobel hace menos probable una solución pacífica y negociada al conflicto venezolano.

La semana pasada, el Comité Noruego del Nobel otorgó el Premio Nobel de la Paz 2025 a María Corina Machado, una destacada dirigente opositora venezolana. Su valentía y firmeza en la lucha por la democracia venezolana merecen reconocimiento. Sin embargo, su apoyo al uso de la fuerza para lograr un cambio político hace que su elección para ser galardonada con el Premio Nobel de la Paz resultara paradójica y preocupante.

El año pasado, Machado galvanizó y electrizó a los venezolanos, acostumbrados desde hacía tiempo a considerar las elecciones amañadas de su país como insignificantes. Desafiando la persecución y el acoso del gobierno, instó a la ciudadanía a usar las urnas para desafiar el régimen autoritario de Nicolás Maduro y ayudó a organizar una vasta red de activistas políticos que recopilaron actas que demostraban que el candidato opositor, Edmundo González, había derrotado a Maduro (a la propia Machado se le había prohibido postularse a la presidencia) . Como dijo con humildad al enterarse del premio, este debe considerarse un homenaje a los millones de venezolanos que se movilizaron para exigir un cambio democrático.

Sin embargo, el Premio Nobel de la Paz no es un premio a la valentía ni a la defensa de la democracia por cualquier vía. Y las declaraciones públicas de Machado—así como sus silencios—en la semana posterior a su recepción demuestran por qué no era la persona adecuada para un galardón diseñado para promover la labor por la resolución pacífica de conflictos.

En la semana transcurrida desde que Machado recibió el Premio, Venezuela y Estados Unidos se han acercado a entrar un conflicto bélico abierto. El gobierno de Trump ha continuado hundiendo embarcaciones cerca de la costa venezolana, lo que ha causado la muerte de al menos 27 personas, a quienes ha acusado—sin pruebas—de participar en el narcotráfico. El presidente estadounidense ha declarado que está considerando ataques terrestres en territorio venezolano y ha reconocido haber autorizado operaciones encubiertas de la CIA en Venezuela—operaciones que suelen implicar la desestabilización y ataques a figuras políticas. El miércoles, dos bombarderos estadounidenses sobrevolaron la costa venezolana siguiendo un patrón que, al ser mapeado, formó una cruda obscenidad, en una clara provocación destinada a obtener una respuesta de la Fuerza Aérea venezolana que, a su vez, podría servir de pretexto para la escalada del conflicto.

Incluso después de recibir el Premio Nobel, Machado ha expresado su apoyo explícito y abierto a estas operaciones, llegando incluso a dedicar el premio al presidente Trump y al pueblo venezolano, elogiándolo por “abordar esta trágica situación en Venezuela como corresponde”, calificando los ataques como acciones de “fuerzas del orden” y afirmando que la oposición llevaba tiempo solicitando dichas acciones. Al preguntársele si apoya una invasión a Venezuela, Machado evita rechazar el uso de la fuerza, afirmando que “Venezuela ya vive una invasión” y que, en cambio, necesita una “liberación”.

El Premio Nobel de la Paz no es un premio a la valentía ni a la defensa de la democracia por cualquier vía. Su propósito es reconocer los esfuerzos orientados a la resolución pacífica de los conflictos.

Nada de esto sorprende. La Machado ha defendido durante años el uso de la fuerza militar para derrocar al gobierno de Nicolás Maduro. En 2020, solicitó a la Asamblea Nacional controlada por la oposición que autorizara la entrada de tropas extranjeras a Venezuela como parte de una operación multilateral para tomar el control del territorio y desarmar a las fuerzas gubernamentales. Incluso después de recibir el premio, declaró al periódico español El País que, para enfrentar una tiranía, se necesitaba “fuerza moral, espiritual y física” y que “poner la fuerza por delante” y una “amenaza creíble” de acción militar eran fundamentales para lograr un cambio político.

También es preocupante la negativa de Machado a condenar las violaciones de los derechos fundamentales de los venezolanos por parte de la administración Trump. A principios de este año, las autoridades estadounidenses deportaron a más de 200 ciudadanos venezolanos a una prisión salvadoreña, acusándolos con escasas pruebas de pertenecer a la red criminal Tren de Aragua, mientras que a muchos de ellos se les negó el debido proceso con el pretexto de ser combatientes enemigos en una invasión a Estados Unidos. Machado respaldó el plan de deportaciones antes de su implementación y guardó silencio incluso ante la creciente evidencia de que se estaban violando los derechos básicos de los venezolanos deportados.

El silencio de Machado respecto a las ejecuciones extrajudiciales de venezolanos en aguas internacionales resulta aún más impactante dado el creciente consenso entre grupos de derechos humanos y expertos legales sobre la ilegalidad de estas acciones. Según fuentes citadas por el New York Times, la preocupación por los asesinatos parece haber influido en la inusual decisión del jefe del Comando Sur de Estados Unidos, el almirante Alvin Hosley, de dimitir tras solo un año de su mandato de tres años.

Machado también ha apoyado desde hace tiempo las sanciones económicas contra Venezuela. Si bien ha argumentado que estas sanciones son necesarias para privar de recursos al régimen de Maduro, la evidencia demuestra que han contribuido a generar el mayor colapso económico en tiempos de paz de la historia mundial y las mayores oleadas migratorias jamás vistas en el hemisferio occidental.

El silencio de Machado ante las deportaciones forzadas y las ejecuciones extrajudiciales de venezolanos revela una inquietante decisión de relegar los derechos de los venezolanos a un segundo plano frente a un objetivo político.

El Premio Nobel de la Paz fue establecido en 1895 para reconocer a quienes han promovido la fraternidad entre las naciones, trabajado por la abolición o reducción de los ejércitos permanentes y fomentado la realización de congresos por la paz. A lo largo de los años, el Comité Nobel ha interpretado este mandato de forma amplia, honrando tanto a líderes mundiales que han liderado esfuerzos para poner fin a conflictos como a activistas de derechos humanos y democracia comprometidos con el cambio por medios pacíficos. El premio a la Sra. Machado rompe con ambas tradiciones al honrar a una figura conocida por su defensa y apoyo al uso de la fuerza para impulsar el cambio político.

Quizás el mayor riesgo de este premio es que, al poner la autoridad moral del premio detrás de quien sostiene una postura de línea dura hacia el cambio político, puede hacer una transición pacífica y negociada menos probable. El premio llega en un momento en que hay un debate abierto, tanto en Venezuela como en círculos de política internacional, sobre la mejor estrategia para promover el cambio democrático . El apoyo de Machado a la acción militar externa y su oposición a cualquier negociación que no resulte en la expulsión completa del chavismo del poder la colocan en un extremo de ese espectro. Otros actores han resaltado la necesidad de continuar la resistencia pacífica organizada, promover la organización electoral y participar en negociaciones centradas en reformas institucionales que hagan posible la coexistencia con el chavismo como estrategias más viables y realistas para el cambio político.

El Comité podría haber honrado al movimiento democrático de Venezuela otorgando el premio a los valientes activistas que recopilaron las actas electorales que ofrecieron prueba de la derrota de Maduro el año pasado.

El Comité Nobel podría haber decidido honrar al movimiento democrático venezolano otorgando el premio a los valientes activistas que recogieron las actas que demostraron la derrota de Maduro el año pasado. Al optar por respaldar a un líder dentro de ese movimiento —y precisamente al líder que más se opone a las negociaciones—, podrían haber hecho menos probable una solución política y más probable una guerra.

Solo en contadas ocasiones el Comité Nobel ha decidido otorgar el premio a un líder político de la oposición a un régimen autoritario. Quizás el ejemplo más cercano sea el Nobel de 1983 otorgado a Lech Walesa, quien desempeñó un papel clave para atraer la atención internacional hacia Polonia y hacer posibles los acuerdos negociados que condujeron a lo que sigue siendo la transición económica y política más exitosa hacia una democracia de mercado en Europa del Este. Al igual que Walesa, Machado se enfrenta ahora a una decisión crucial: si utilizar su prestigio para reconciliar a una nación fracturada, o contribuir a profundizar aún más sus divisiones.

Sanctions and Venezuelan Migration

This paper examines the potential impact of different US economic sanctions policies on Venezuelan migration flows. I consider three possible departures from the current status quo in which selected oil companies are permitted to conduct transactions with Venezuela’s state-owned oil sector: a return to maximum pressure, characterized by intensive use of secondary sanctions, a more limited tightening that would revoke only the current Chevron license, and a complete lifting of economic sanctions. I find that sanctions significantly influence migration patterns by disrupting oil revenues, which fund imports critical to productivity in the non-oil sector. Reimposing maximum pressure sanctions would lead to an estimated one million additional Venezuelans emigrating over the next five years compared to a baseline scenario of no economic sanctions. If the US aims to address the Venezuelan migrant crisis effectively, a policy of engagement and lifting economic sanctions appears more likely to stabilize migration flows than a return to maximum pressure strategies.

Scorched Earth Politics and Venezuela’s Collapse

Between 2012 and 2020, Venezuela’s per capita income declined by 71%, the largest peacetime economic contraction documented in the Common Era. I estimate that the severing of the country’s links to global trade and financial markets explains 56% of this contraction. I propose an explanation of Venezuela’s economic collapse as a consequence of the incentives of political actors to adopt strategies that generate severe negative economic externalities. In the absence of politically-induced restrictions on access to global markets, Venezuela would have experienced a contraction of 32% in per capita income, in line with those of other policy-induced growth collapses

Venezuela Negotiations: Light at the End of the Tunnel?

Wednesday, January 25, 2023. 12:00 a.m. – 1:30 p.m.

The Forum SIE Complex, Denver University, Colorado.

Speakers:

Carolina Jimenez Sandoval President of the Latin American Office for WOLA

Michael Penfold Global Fellow in the Latin America Program, Wilson Center

Luis Vicente Leon President, Datanalisis

Moderator:

Francisco Rodriguez Director, Oil For Venezuela. Rice Family Professor Josef Korbel School, Denver University

Sanctions and Oil Production: Evidence from Venezuela’s Orinoco Basin

Wednesday, March 3, 2021. 12:30 pm.

Virtual event

Speakers:

Francisco Rodriguez Director, Oil For Venezuela. Rice Family Professor Josef Korbel School, Denver University

Conference on Venezuelan Politics: Quantifying Venezuela’s Destructive Conflict

Friday, October 18, 2024. 1:30 a.m. – 2:30 p.m.

Chicago Booth Harper Center Room C05, University of Chicago, Illinois.

Speakers:

Francisco Rodriguez Director, Oil For Venezuela. Rice Family Professor Josef Korbel School, Denver University

Osmel Manzano Adjunct Professor, Walsh School of Foreign Service, Georgetown University. Elliott School of International Affairs, George Washington University

Chang-Tai Hsieh Phyllis and Irwin Winkelried Distinguished Service Professor of Economics and PCL Faculty Scholar, University of Chicago

Moderator:

Jennifer McCoy Professor, Georgia State University

July 28th election and the future of US-Venezuela relations

Sunday, March 25, 2024.

Speakers:

Jose Chalhoub Political risks and oil consultant

Elias Ferrer Director, Orinoco Research

Francisco Rodriguez Director, Oil For Venezuela. Rice Family Professor Josef Korbel School, Denver University

Un Pacto por el Futuro de Venezuela

Wednesday, February 21, 2024. 12:00 a.m. – 1:30 p.m.

Hotel Lido Caracas, Salón Doral II.

Speakers:

Francisco Rodriguez Director, Oil For Venezuela. Rice Family Professor Josef Korbel School, Denver University

Venezuela’s Long Crisis

Monday, December 11, 2023. 12:00 a.m. – 1:30 p.m.

The Pivot Globely News Podcast

Interviewed:

Francisco Rodriguez Director, Oil For Venezuela. Rice Family Professor Josef Korbel School, Denver University

Host:

Arif Rafiq President, Vizier Consulting